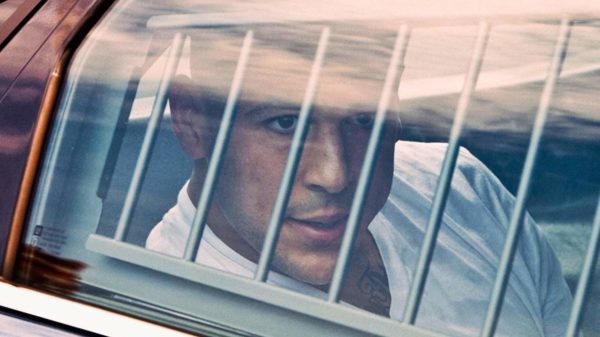

In 2013, Aaron Hernandez, a rising young superstar tight end for the New England Patriots NFL football team, shot to death his friend Odin Lloyd in cold blood, shocking the sporting world. Hernandez was convicted for the murder and sentenced to life in prison without parole.

In 2017, weeks after being acquitted for a 2012 double homicide in Boston and two days after being outed as gay on a sports talk radio program, Hernandez, 27, committed suicide by hanging himself in his prison cell.

Since then, numerous articles, books and true crime documentaries have attempted to solve the mystery of Aaron Hernandez, the heavily tattooed tight end who played in the NFL by day and the mean streets by night.

The ambiguity swirling around the former Patriot isn’t just a whodunit, it’s a “why do it?” Why did a professional athlete with a $40 million contract with one of the NFL’s premier teams kill his friend, allegedly kill two strangers in a drive-by shooting and allegedly shoot his pot-and-gun dealer in the face?

Netflix’s runaway hit true crime docuseries, “Killer Inside: The Mind of Aaron Hernandez,” is the latest and most thorough attempt yet to examine the many facets of the late convicted murderer’s life, including his sexuality, the untimely death of his father when he was 16 and the numerous concussions he incurred playing football, to show how they may have helped transform a seemingly happy-go-lucky standout high school athlete into an impulsive killer in the short matter of a half-dozen years.

Working with reporters from the Boston Globe’s Spotlight team, executive producer Geno McDermott presents the story in three parts: Hernandez’s childhood and youth growing up in the small, relatively peaceful town of Bristol, Connecticut; his three seasons playing for the University of Florida in Miami and his two seasons with the Patriots.

The story is told through sports and news footage, interviews with family members, teammates and victims, as well as hundreds of prison telephone conversations between Hernandez and his family, friends and attorneys obtained by the Globe.

In order to explore how Hernandez’s sexuality might have affected his behavior, McDermott enlisted Redding native and former NFL offensive lineman Ryan O’Callaghan, one of a handful of former NFL players who’ve come out of the closet after their playing careers ended.

“I was approached by Geno,” O’Callaghan told me on the phone last week. “My roll was to present the perspective of a closeted NFL player and the things that you deal with.”

O’Callaghan, who played for the Patriots and Kansas City Chiefs during a six-year, injury-riddled NFL career that ended in 2011, published his courageous coming out story last year, “My Life on the Line: How the NFL Near Killed Me and Ended Up Saving My Life.”

O’Callaghan realized he was gay by junior high school and feared he’d be rejected by his family and friends if they found out. So, he began building a straight persona. From Enterprise High School on, football was his “beard,” a slang term for a woman who dates a gay man to help him maintain a straight appearance.

Every waking moment that wasn’t devoted to playing football was spent maintaining his fake straight identity. He vowed to kill himself when his football career ended, rather than live openly as a gay man, and came perilously close to fulfilling that promise via a handgun and a lethal opiate addiction.

If an experienced Kansas City Chiefs trainer hadn’t encouraged O’Callaghan to seek mental health treatment, he might not have lived to tell the tale. It appears Aaron Hernandez never received such encouragement, perhaps because the escalation of his crimes was so rapid, his Patriot minders couldn’t keep up with him.

Hernandez’s sexuality remains a matter of some conjecture three years after his suicide. The athlete/killer never came out publicly, and O’Callaghan was quick to tell me, “As I stated in the film, the last thing I’m going to do is out someone. I can safely say that if he was gay, it certainly complicated his mental status.”

“Killer Inside” makes a fairly strong case that Hernandez was indeed gay or bisexual. One of his attorneys during the double-murder trial raised the issue with Hernandez after the prosecution threatened to a claim Hernandez’s sexuality, and his need to keep it secret, was a contributing factor in the crime. Hernandez reportedly told his fiancé and the attorney he was gay, but prosecutors dropped the tactic and the subject never came up at trial.

However, it was leaked to a reporter who then hinted about Hernandez’s sexuality on a Boston sports talk radio program, which after the former Patriot’s prison suicide ignited a flurry of speculation in local and national tabloid media. Kyle Kennedy, a heavily tattooed habitual criminal on the same cell block with Hernandez, claimed to be the fallen football hero’s jailhouse lover. Many of Hernandez’s former fans, still reeling from his murder conviction and his acquittal on the double-homicide charges, were in disbelief.

The lurid media whirlwind eventually prompted Dennis SanSoucie, the quarterback on Hernandez’s high school football team, to come out of the closet and admit that he’d had an on-and-off- sexual relationship with Hernandez throughout junior high and high school. SanSoucie’s recollections of smoking marijuana with Hernandez before school and games is one of the few light-hearted moments in “Killer Inside.”

“We walked right up to the school, like King Shit,” he says in part 1 of the documentary. “Quarterback, tight end, stone happy. We used to love horse-playing and having fun with each other because we were just kids full of life.”

They also engaged in secret extra-curricular sexual activities throughout the time period. According to SanSoucie, they didn’t consider themselves or what they were doing “gay.”

“I was in such denial, because I was an athlete,” he said. “‘You mean to tell me that the quarterback and the tight end was gay? He sleeps with other men?’ No, it doesn’t sit right with people. It doesn’t sit right within our own stomach at that time.”

This is where O’Callaghan makes the first of four appearances in the documentary, and it’s apt timing. Like Hernandez and SanSoucie, by junior high school, he knew he was attracted to males. Like Hernandez, O’Callaghan grew up in a home environment hostile toward gays, although it must be said his family preferred ridiculing gays with jokes, while Fernandez’s father, according to SanSoucie and Hernandez’s older brother, would literally “slap the faggot out of you.”

The refusal or inability to conform to forced societal norms causes what psychologists call minority stress. In O’Callaghan’s case, this stress was so pronounced, he never acted on his own sexual desires for fear of being caught and exposed until well after his football career ended. In the documentary, he suggests Hernandez, if he did act on his sexual desires, had that many more secrets to keep, and thus that much more stress.

It’s a reasonable conclusion, and when combined with other elements in Hernandez’s short life presented in “Killer Inside,” a clearer picture of why he did what he did begins to take shape.

His strict father, who had been a local football hero in his own time, may have been homophobic, but Hernandez still revered him and longed to follow in his footsteps at nearby U-Conn. His father’s unexpected death due to an infection contracted after hernia surgery when Hernandez was 16 sent the young athlete on a six-year-long tailspin.

In the aftermath of his father’s death, Hernandez gravitated toward an older female cousin, just as his recently widowed mother, a local public school teacher, switched her affection to said cousin’s husband. Said cousin lived in a seedier part of Bristol, introducing Hernandez to the small town’s criminal element.

The documentary doesn’t state it, but this is apparently where Hernandez developed a fascination with guns that would eventually become a collection of pistols and assault rifles rivaling the average doomsday prepper’s.

Tearing up his contract with U-Conn after his father’s death, Hernandez instead left high school early to play for the University of Florida at age 17. His first reported violent act under Christian coach Urban Meyer was the sucker punching of a Miami bartender, bursting his eardrum, after he’d requested that the underage athlete pay for the two drinks he’d consumed. Hernandez’s minder that night was Gators teammate and renowned puritanical Christian, quarterback Tim Tebow.

No charges were filed, and the incident was swept under the rug. Meyer, Tebow and Hernandez would team up for one national collegiate championship, but by the tight end’s junior year in college, the writing was on the wall: Aaron Hernandez was a phenomenal force on the playing field, but his erratic and sometimes violent behavior off the field precluded his future at the University of Florida.

So, Hernandez entered the NFL draft one year early in 2011 and was ignominiously selected by the New England Patriots in the fourth round. The rookie soon proved his value as his speed, size and ability to catch the ball rivaled his fellow rookie tight end, Rob Gronkowski. Coach Bill Belichick designed a two tight end offensive set that quarterback Tom Brady utilized to destroy defenses on the Patriots 13-3 run to Super Bowl XLVI.

The Patriots lost to the New York Giants, but Hernandez, 22, caught a touchdown pass, making him one of the youngest players to ever score in the Super Bowl.

O’Callaghan played three seasons with the Patriots before Hernandez’s arrival in New England and notes in the documentary that Belichick’s legendary attention to detail made the team an excellent place for a closeted player such as himself to hide out. No distractions were permitted, and that suited O’Callaghan’s unsettled mind perfectly.

From the outside, it appeared that Hernandez’s immersion in the Patriots’ system had done him some good during his first season. Such was not the case. Shortly after signing with the Patriots, Hernandez began hanging out with convicted felon Alexander Bradley, known to Boston police as a big-time marijuana and illegal gun dealer. Seven months after the Super Bowl, the pair were out clubbing in Boston when, according to Bradley, a man accidentally spilled his drink on Hernandez.

According to Bradley, Hernandez was incensed, and waited for the man and his friend, both of whom turned out to be Haitian immigrants, to leave the club. As they drove away, Hernandez and Bradley followed the men in a rented SUV. At Hernandez’s double-homicide trial, Bradley testified that they pulled up alongside the car and Hernandez emptied his revolver into it, killing both men.

The Haitian men worked cleaning offices at night and had no known criminal affiliations. Boston police were befuddled by the seemingly motiveless violent crime. One month after the double-murder, the Patriots rewarded Hernandez with a $40 million contract for his performance on the field. He went on to have a successful second season with the Patriots, although the team didn’t make the Super Bowl.

In February 2013, Hernandez and Bradley traveled to Miami. Bradley testified that after a long night of partying at a strip club, he fell asleep in the passenger seat while Hernandez was driving them home. When he woke up, Hernandez was looming over him, pointing a gun in his face. He pulled the trigger, shooting Bradley in the face at point-blank range. Hernandez dumped him on the side of the road, but incredibly, Bradley, who lost the use of his left eye, survived.

Bradley, planning personal revenge, at first refused to tell police who shot him, and Hernandez once again skated free from the sort of trouble that would have caught the Patriots’ attention. It was not to last.

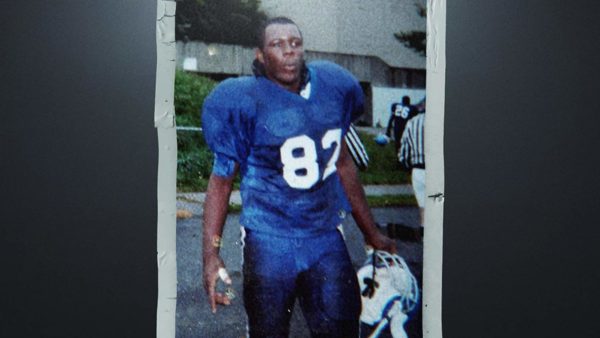

Semipro football player Odin Lloyd’s misfortune was that his fiancé happened to be the sister of Hernandez’s fiancé. That’s how Lloyd and Hernandez met, and they bonded over their love for weed—Lloyd’s nickname was “Blunt Master”—and football. In June 2013, for reasons that remain murky, Hernandez viciously shot and killed Lloyd, dumping the body not far from Hernandez’s mansion.

It was a cowardly, cold-blooded killing. Hernandez made no effort to cover his tracks and was quickly arrested and charged with murder. He was immediately fired by the Patriots; the team encouraged his fans to trade in their Hernandez jerseys for free.

Like Hernandez’s other violent actions depicted in “Killer Inside,” Lloyd’s murder was senseless. Irrational. Premeditated, yet impulsive at the same time. The only known motive is that Hernandez felt Lloyd had become “disloyal.” About what remains uncertain. One of Lloyd’s semipro football teammates describes Hernandez as a “crasher,” a type of wannabe gangster who lashes out with extreme violence because he doesn’t know the first thing about the streets.

As “Killer Inside” weaves back and forth through Hernandez’s life and crimes, a pattern of escalating impulsive violence emerges. From sucker-punching a Miami bartender at age 17, to an alleged drive-by shooting in Miami at age 19, to the alleged double-homicide in Boston and alleged shooting of Bradley in the face at age 22, to Lloyd’s murder at age 23, Hernandez steadily ramped up the violence, in a relatively short period of time.

The death of Hernandez’s abusive but revered father and the break-up of the family home when the young athlete was just 16 undoubtedly helped set his downwardly spiraling trajectory. The mental and physical pressures of playing college and then professional football at the highest level were immense. Add to that the pressure of playing as a closeted gay man in America’s most macho sport, and it’s not hard to see Aaron Hernandez had a lot on his young mind.

These factors don’t excuse Hernandez’s violent behavior, but they go some way toward explaining why he might have behaved the way he did. A final factor is introduced in part 3 of the documentary, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, CTE, the neurodegenerative disease caused by repeated blows to the head incurred playing sports such as football.

As O’Callaghan notes during the segment, he’s had six shoulder surgeries, two knee surgeries and countless concussions. That was considered normal in the NFL until fairly recently.

After Hernandez committed suicide, his brain was donated to scientists studying CTE. Upon examining it they found the most advanced case of CTE they’d ever seen in a 27-year-old. “Killer Inside” documents the damage with film of Hernandez suffering severe concussions at the high school, college and pro level.

CTE is associated with impulsive violent behavior in some people, and according to one of Hernandez’s prosecutors interviewed in the docuseries, the disease offers a plausible explanation for crimes that otherwise remain inexplicable.

Even with all of these factors combined, “Killer Inside” concludes Hernandez was ultimately responsible for the poor decisions he made and the violent acts he committed. We don’t know enough about CTE to definitively say it played a role in his violent turn, as the documentary states. Hernandez told one of his attorneys and his prison lover that he struggled remaining closeted, but we don’t know if his battle was as extreme as O’Callaghan’s, recounted in grim detail in his book “My Life on the Line.”

We don’t even know how many people Hernandez killed. He was convicted for Lloyd’s murder and acquitted for the Boston double-homicide but bragged to his prison lover he had killed four people.

Unlike more exploitative true crime shows, “Killer Inside” gives equal time to the friends and families of Hernandez’s victims and alleged victims. Their grief and anger are palpable and interspersed throughout the three episodes. There’s no attempt to make excuses for Hernandez. Instead “Killer Inside” offers us some explanations and some “what ifs.”

What if he’d never played football and suffered countless concussions?

What if he’d received proper counseling after the death of his father?

What if it was easier to be an openly gay player in high school, college and the NFL?

What if his coaches at the University of Miami had held him accountable for his actions?

These “what ifs” will mean little to people who see Hernandez as a tattooed killer thug who got his just deserts. However, they do offer hope for preventing future Aaron Hernandezes, and that’s what makes “Killer Inside” a cut above most true crime documentaries. This isn’t something we want to happen again. Hernandez’s fall from such exalted heights is both astonishing and frightening to witness.

With the San Francisco 49ers and the Kansas City Chiefs facing off in the Super Bowl this Sunday in Miami, it’s a sobering reflection on the sport and culture of football.

O’Callaghan famously doesn’t like the game of football, never did. It was just a beard, a cover, a mask he no longer needs now that he’s out.

Nevertheless, he’ll be at the Super Bowl, hosting a group of LBGTQ youth before the Super Bowl in Miami this Sunday. “It’s one of those things the league does that nobody knows about,” he told me on the phone.

O’Callaghan said he recently spoke to NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell, at Goodell’s urging, on the subject of what the league can do to be more inclusive of gay players. O’Callaghan remains cautiously optimistic meaningful change will actually be implemented in the league.

He’s pleased how his quotes were used and edited in “Killer Inside.” The responses on social media have been mostly positive. His main goal for participating was to generate publicity for the Ryan O’Callaghan Foundation, which seeks to open doors for LGBTQ athletes to participate openly in college and professional athletics. He’s still catching up with potential individual and corporate donors who’ve contacted him since the docuseries was released Jan. 15.

Eventually, O’Callaghan plans to provide scholarships to LGBTQ athletes, but for now he’s focusing on opening doors by sharing his own experience, as he did earlier this month at a Shasta College event sponsored by the Shasta-Tehama-Trinity County ACLU.

“It was a very welcoming crowd,” he said, adding with a chuckle: “The conversations afterward got a little political, naturally.”

O’Callaghan caught me off guard by asking who I favored in the Super Bowl. “The 49ers!” I blurted out like the rabid fan I am. “At least you’re loyal,” he said, admitting he had some interest in the outcome, since his former team the Chiefs are playing.

But he still doesn’t like football. He’ll be flying out of Miami before the game starts.